THE HISTORY OF BPR & EARLY ADOPTER FORD MOTOR COMPANY

Outlined below is the history of Business Process Re-engineering. The example of early adopter Ford Motor Company is used to illustrate the tremendous benefits of radical changes in policies, procedures, and workflow governing administration of functions critical to an organization’s success.

THE IMPETUS FOR BUSINESS PROCESS REENGINEERING -

THE INEFFICIENT PAPER-DRIVEN NATURE OF HISTORICAL WORKFLOW PROCESSES

Spurred by the Industrial Revolution, the size of business organizations grew immensely; to operate effectively, it was necessary to break business functions into subcomponents each of which required specialized expertise. Functions of a similar nature were assigned to the same department.

Discrete processing rules were promulgated to permit entry level processing clerks to complete repetitive tasks with little autonomy. Specialized forms were designed to structure and record work as well as to facilitate inter-departmental communication. Detail of work completed by one department was transmitted to another using the completed paper forms; this permitted an effective “hand-off” between the various departments.

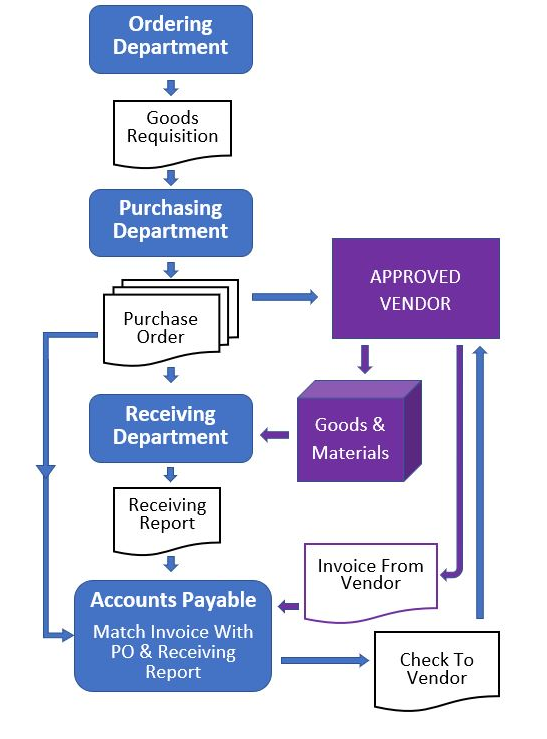

The graphic at right is a depiction of the Goods Acquisition Process still in existence is some organizations. Forms depicted are a Goods Requisition, a Purchase Order, a Receiving Report, a Vendor Invoice submitted by the vendor for payment of goods and/or materials supplied to the organization, and a Vendor Check.

The workflow diagram is considerably simplified and as such greatly understates the level of human resources actually required to effectuate the purchase of goods and services; completing these four documents required input from five supervisors, two senior clerks, and five lower-level clerks at a minimum. Under this historical workflow model, growth in revenue required hiring additional supervisors and clerks.

Early Efforts to Automate Historical Workflow Processes

Early automation efforts computerized repetitive tasks including performance of manual calculations as well as typing of the Vendor Check. Errors were curtailed and the need for clerical resources was, to a limited degree, diminished.

Subsequent automation efforts produced computer generated paper forms - virtually the same Goods Requisition, Purchase Order, and Receiving Report previously handwritten. These continued to be passed sequentially between four departments as depicted in the Goods Acquisition Process flowchart above.

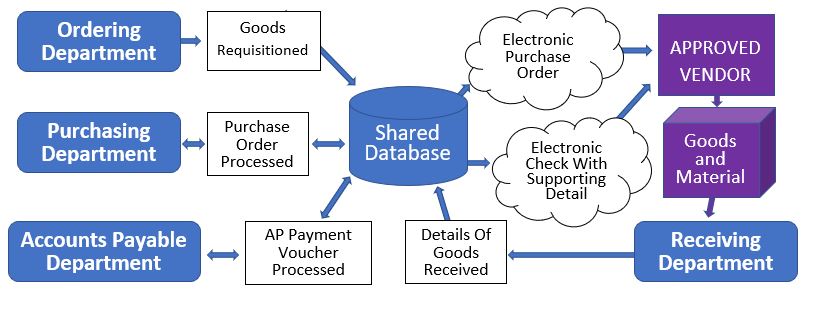

The graphic at right symbolizes this intermediate result. Paper forms generated by independent systems continued to form the foundation of each inter-departmental handoff. Significant inefficiencies remained built into the workflow model. As such the trajectory of increase in variable costs, necessary to fund support functions as revenue increased, was bent – but not appreciably.

Full integration of independent subsystems using a shared database brought further cost savings. It became readily apparent that further investment in automation of the historical workflow model brought diminishing returns.

BUSINESS WORKFLOW REIMAGINED:

FORD MOTOR COMPANY'S REENGINEERED GOODS ACQUISITION PROCESS

As noted above, full automation of workflow processes put in place at the dawn of the industrial revolution did not break the linear relationship between revenue and variable costs. Simply put, as revenue increased a commiserate increase in variable costs (such as administrative salaries) was necessary. This fundamental fact led Michael Hammer to conclude that organizations needed to search for a new paradigm - to examine, reimagine, and reengineer policies and procedures to affect the most efficient workflow possible.

Spurred by the need to cut costs Ford Motor Company set a goal of reducing the size of its Accounts Payable Department headcount by 20% - from 500 to 400. Its preliminary study revealed that Mazda, a smaller competitor, had only 5 people in the accounts payable area; accordingly, Ford adjusted its goal to achieve a headcount of only 100 supervisors and clerks – a reduction of 80%. The firm realized that to achieve this ambitious goal it would need to expand the scope of its project to include the Goods & Materials Acquisition process as a whole.

(As noted elsewhere, Michael Hammer first proposed the conceptual underpinnings of Business Process Reengineering; the principles which would define the field were codified in Reengineering the Corporation, co-written with James Champy.)

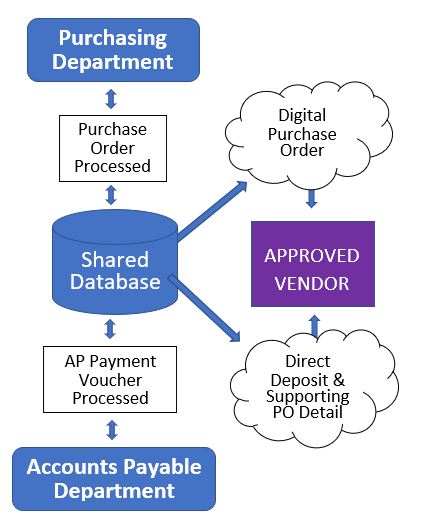

The diagram at right depicts Ford’s reengineered Goods & Materials Acquisition model. Clearly evident, when compared to the flowchart above, is the use of a shared database as well as full integration of all departmental subsystems. Equally apparent is the extension of the system’s digital output beyond the organization to include electronic transfer to vendors of Purchase Order details as well as Direct Deposit of amounts due in lieu of payment by Vendor Check. Ford’s design enabled it achieve a near paperless office an end result of automation first predicted by in “The Office of the Future”, an article published in a June 1975 edition of Business Week.

Business Process Reengineering: Radical Change Resulting In Dramatic Benefits

An examination of the objectives behind current processes is key to any successful business process reengineering effort. Once fully understood the validity of continuing to pursue each objective can be evaluated. New more efficient and effective ways to achieve validated objectives must be discovered. Paramount this effort is examining the inefficiencies inherent in current processes and procedures.

Ford found three main objectives to be the pillars of the Goods & Materials Acquisition function:

- To order, from an approved vendor, goods & materials necessary to sustain both operations and administrative support activities

- To account for the receipt of goods & materials meeting required specifications in the quantity ordered

- To renumerate vendors for goods & materials received and accepted by the organization at agreed upon pricing

Each of the objectives was found to be valid. However, significant inefficiencies were found in processes employed by the Accounts Payable Department.

As depicted in the first workflow diagram these inefficiencies included matching the quantity and vendor part number of each item on the Receiving Report with that on both the Purchase Order and the Vendor Invoice. Additionally, the unit price of each item on the Purchase Order was matched to the unit price on the Vendor Invoice. In total up to 15 data items were required to be matched. Each discrepancy found led to an investigation that was both cumbersome and costly. Inconsistencies were resolved through time consuming consultation with other departments and/or the supplying vendor.

Error Elimination & Discrepancy Resolution - at the Source. Ford endeavored to prevent errors by pushing the matching process to the source – effectively ensuring that any discrepancy was addressed and resolved when first discovered. For example, resolution of a discrepancy in quantity received vs quantity ordered would be addressed by the Purchasing Department immediately upon details of goods received being scanned or entered.

Digital Purchase Order level detail, documenting quantities received and unit prices agreed to, was transmitted to Ford’s vendors to directly support electronic payments made. Vendors were responsible to resolve disparities, if any, between electronic payment received and payment expected. In effect, Ford transferred resolution of differences between quantities received and quantities for which payment was sought from its Accounts Payable Department to the Vendor.

Ford pared its procedures to the minimum required to meet its objective “to renumerate vendors for Goods & Materials received”. Its reengineered procedures focused, not on goods invoiced by the vendor, but on good received by its organization.

Full System Integration. The image at right was used in an earlier discussion of early efforts to automate historical workflow processes. Again it is meant to depict disparate department-based systems which produce paper forms that, like their handwritten predecessors, are used to support inter-unit workflow handoffs.

Evident in the flowchart of the Ford's reengineered Goods and Materials Acquisition workflow, is the use of a shared database around which fully integrated departmental subsystems were built. Goods Requisition data generated from sales, operations, and manufacturing systems, or entered by an individual if required, is stored at a level granular enough to permit application of valid financial and departmental account numbers once goods have been received. Periodically, the Purchasing Department subsystem automatically aggregates requisition data by line item and generates a partially completed electronic Purchase Order.

A Purchasing Department clerk can then retrieve the partially completed Purchase Order to make modifications even to include merging in additional requisition data. Once finalized, the purchasing clerk "releases" the completed Purchase Order for transmittal to the selected vendor.

Similarly, the Accounts Payable Department subsystem aggregates Purchase Order data, previously matched to Receiving Report data, to build substantially completed batches of AP Payment Vouchers. An Accounts Payable Department clerk can retrieve the data and make modifications as required before releasing the AP Payment Vouchers which are then automatically aggregated to produce transmittal of a Direct Deposit to the appropriate vendor. Simultaneous to Direct Deposit data being transmitted to the vendor's bank, supporting documentation, detailed by Purchase Order, is transmitted to the vendor.

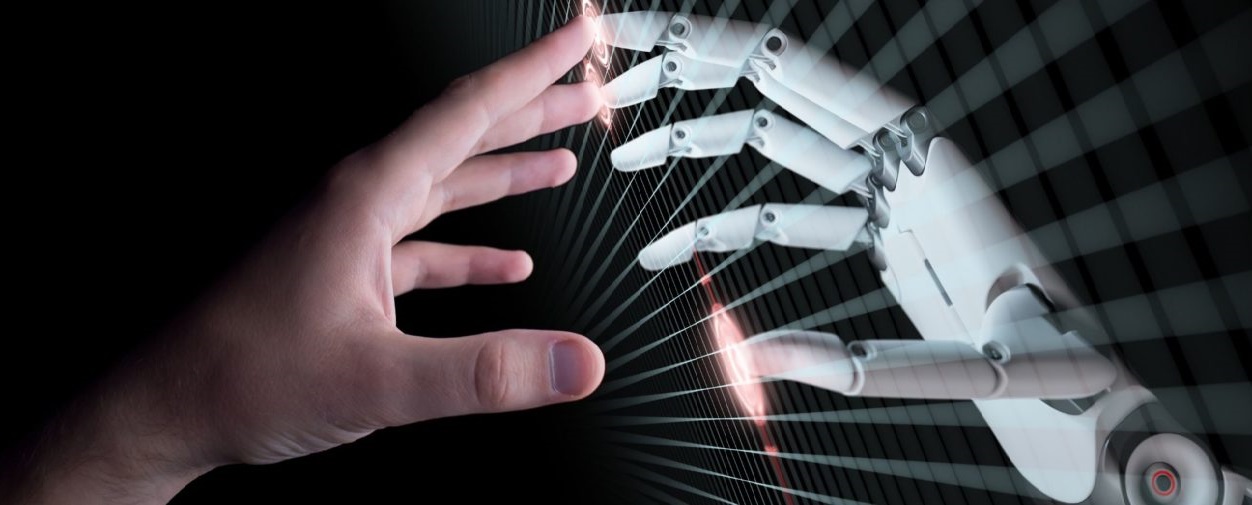

The image at right depicts the machine interface afforded each user of a fully integrated system. Manual handoffs have been replaced by user-system interfaces resulting in a substantially reduced error rate, increased staff productivity, and significantly reduced costs.

Simplification and Streamlining Through Reengineering. The objectives of Simplification and Streamlining are most often intertwined. When accomplished through Business Process Reengineering, particularly when coupled with integration, the combined impact of achieving the objectives of each are dramatic.

A pared-down version of the flowchart depicting Ford's reengineered Goods and Material Acquisition process is depicted at right.

The previous section outlined several automated processes that aggregate data from one source which is then made available to another department or unit. Such processes are inherent in the Purchase Order processing subsystem as well as the AP Payment Voucher processing subsystem.

Vendors selected to fulfill goods or material orders are restricted to those in the approved Vendor File; unit pricing is retrieved from the Vendor Item Catalog File which also holds item codes cross-referenced to those used internally by Ford. Electronic aggregation, automated calculation, and automated reference to available enterprise data permit manual processes to be simplified and streamlined to the maximum degree possible.

Processes developed to enhance functionality in Purchasing Department and Accounts Payable Department sub-systems enabled both simplification and streamlining of workflow. As noted, such automation includes generation of a digital Purchase Order. This feature permits the vendor to begin fulfilling an order immediately upon approval by the organization. The resulting reduction in lead time enables lower stock levels to be maintained.

Additionally, enhancements to the Accounts Payable Department subsystem permit generation of Direct Deposit as well as transmittal of supporting payment detail at Purchase Order level. The former permits Ford to make payments "just in time" to qualify for discounts afforded under vendor terms. The later permits invoice-less payment processing thus ensuring that payments are made solely on the basis of goods and materials received.

Dramatic Results. Ford was able to reduce its FTE headcount from 500 to 125 - a savings of 75%. This dramatic outcome could not have been achieved from further enhancements to its existing systems which were based on a historical model of procuring goods and materials. Significant cost reductions of this magnitude were achievable only after Ford, through Business Process Reengineering, created a new more efficient goods acquisition workflow and tailored its systems to fit that model.